The machineries of joy

Sarah Hoyt is one of those blog friends who’ve become rare and valued friends offline. Like many other first-generation Americans, she has a special appreciation for our freedoms borne of having grown up elsewhere. She can get good and cranky about the current state of things, but she’s inquisitive and hopeful about the future. And she’s wicked, witty fun even before the Scotch starts flowing.

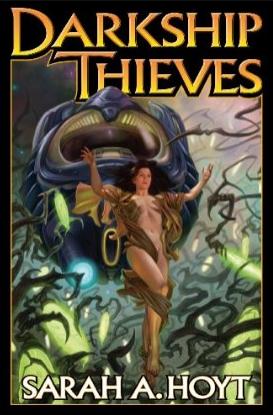

Her day job (and, judging from the hour at which an e-mail sometimes arrives from her, her night job, too) is as a sci-fi and fantasy writer, and her optimism is evident in her writing—there’s mischievous good humor on nearly every page. Like real life, the worlds Sarah creates come with evil forces that persons of good will and fortitude have to fight. And they win. Her most recent book, the first in a space-opera series, is

Darkship Thieves

, and the following is a sort of companion piece she kindly offered to let me publish here about why being optimistic, and not just cranky, about technology is the right attitude.

Her day job (and, judging from the hour at which an e-mail sometimes arrives from her, her night job, too) is as a sci-fi and fantasy writer, and her optimism is evident in her writing—there’s mischievous good humor on nearly every page. Like real life, the worlds Sarah creates come with evil forces that persons of good will and fortitude have to fight. And they win. Her most recent book, the first in a space-opera series, is

Darkship Thieves

, and the following is a sort of companion piece she kindly offered to let me publish here about why being optimistic, and not just cranky, about technology is the right attitude.

*******

Death. Turmoil. Despair. Disaster surrounds us on every side, a precipice threatening to swallow us with its dark and relentless horrors.

Just talk to anyone. Ask them what they expect of the future and you’ll get Ecclesiastes. No one wants to go around bouncing and smiling and telling everyone to cheer up because the future is almost certainly better than the present.

No one goes around saying that, but it is true nonetheless. Sure, of course, some periods in history in some places on Earth have been terrible or disgusting, or sometimes both. But taken as a continuum, the human condition of the majority of normal people on Earth has been a slowly ascending line. So that we are now, in aggregate, the best fed, healthiest, wealthiest humans in history. Which is why expecting the future to bring us horrors untold is a little daft. Or an attempt to sound interesting and thoughtful and get tenure and grants and big book advances.

I suspect the other reason for it is a real sense of angst due to accelerating change. I can’t even imagine how my children will live when they are my age. To be honest, I’m not too sure about how I’ll live in ten years. We haven’t even yet seen all the results of the innovations of the last ten years.

Take the Internet. Ten years ago it was already here, but as one resource among many and worse than a lot of them. Even I, who was an early adopter—my husband being a techno-geek—did only a few things online. I got email—mostly from editors and family. I read a few message boards. And I looked at my library catalogue. Today I read all my news online; I read a good deal of my fiction on line too. Via email and chat programs, I have as much—occasionally more—of a social life online as face to face. I do my preliminary research for work online. I shop on line for specialty items—such as older son’s size 17 shoes—which would otherwise be impossible to find in a medium-size town in Colorado. The list goes on, and I’m sure you know it as well as I do.

So—answer me this—what social changes will result from the Internet? Look beyond what it was designed to do and at what it is obviously doing—or could do.

First, the obvious—the Internet allows one to pick friends who have the same interests and opinions, something those of us in smaller towns might not find in our immediate neighborhood or in our professional lives. Given a few more years, it is quite possible it will allow us to seal ourselves hermetically in our comfort zones and never stray out of them. A few more years still, and I can see several cultures with their own lingo and beliefs so distinct that they will necessitate interpretation for outsiders. (The gentleman in the third row—yes, you, with the glasses—I heard that “But we already have computer professionals!” Be nice. They do try to translate. It’s not their fault our eyes glaze over.)

Then the slightly less obvious—what effect will the Internet have on future generations? In past centuries, given the limited selection, outliers often married people who were not outliers, or didn’t marry at all. This meant a certain genetic reinforcement toward what was considered normal in the given society, physically and—more importantly—mentally. Now I know several couples who met, dated over the Internet and married across the world. About half of them have children. Will the continuation of this trend cause humanity to speciate? Will certain odd characteristics accumulate in a sub-group till it’s no longer part of the human race?

I don’t know. What I know for sure is one thing: that the rate of acceleration of technology is increasing, as future discoveries build on the past ones. It’s no use at all my worrying about the future impact of the Internet, as though it were the only thing that will be different in the future, because other innovations I can foresee are just about to hit—life extension; gene modification; easier acquisition of knowledge. And then there are myriad other innovations I can’t foresee but that are coming as surely as the ones I mentioned.

People sense this at some level. It is a great part—I think—of what fuels the widespread panic about the future. In his small portion of the world, just about every one of us finds himself unable to predict where he’ll be in the future. By which I mean the very near future. Within the next ten years or less. My own profession is beset by the ease of e-publishing, the collapse of traditional bookstores (and that’s more the effect of Amazon and online used bookstores than of ebook readers, whose effect won’t be seen for some years yet), the collapse of the traditional power structure from publishers to distributors to bookstores. Everything is in flux. No one knows what the winning model for the future is. My dentist—talking about something else—mentioned he doesn’t know what he’ll be doing in ten years. You see, turns out you can implant a tooth-bud in the gum, and the tooth will grow and replace the one that has a cavity or is decaying. The technology, he says, will be available for human use within ten years. A friend of mine is married to a man who studies how to clone eyes, so he can replace the eyes of middle-aged people. I wonder how that makes my eye-doctor feel.

Our brain is simply not adapted to these conditions. I recently watched a Terry Pratchett movie and heard humans described as the place where rising ape met falling angel. I don’t think he meant it theologically, since Pratchett is not religious. It doesn’t need to be religious to make sense. We are all of us made of the rational part of our brain, which looks head on at developments and decides what they mean. And then we’re composed, also, of instincts, impulses, and tendencies that we carry around because they were useful to our ancestors.

One of my friends has a sign on her wall that I can’t quote verbatim but that says something about her being a gatherer while her husband is a hunter, which explains their different approaches to buying shoes. It’s funny, but it’s probably also true, in that their ancestors developed different approaches to dealing with life. Take women’s tendency to congregate in vast social women-only groups—please, do take it; I don’t want it—that enforce internal conformity and mutual “defense.” It was probably born of something we see in the most primitive tribes, where women do their gathering in vast groups and watch the kids collectively. Be the pissy woman—hi, everyone—who will not conform and wear her bone on her nose just the way every other woman in the tribe does, and the other ones are liable to neglect to tell you when your toddler is wandering off into the forest while you are busy picking berries.

Or take socialism—I’m quite done with it—which is a system that makes perfect internal sense to us because it works in very small groups and in an economy of extreme scarcity, which is what our ancestors lived in. The groups that insisted the haunch of mammoth be divided among everyone in the tribe, even the pregnant women and the children, left more descendants than the others, and so we are running around with the idea of a fixed economic pie in our minds, and the suspicion that if someone has more than we do, they must have stolen it. These built-in assumptions are probably partly created by the way our brains are formed (no, I don’t understand it either, but one of my friends is a biologist, and he seems to believe it might be so) and partly by deep-set culture: ideas so old and unexamined that they are passed in language and in gesture. The fact that our thinking brain has plenty of examples of redistribution and zero sum economics creating misery and death doesn’t seem to make any difference, against that kind of programming.

The ape is what is screaming, right now, shaking his club in the face of the approaching future, running into the cave and trying exorcism rituals as the ground trembles and shifts beneath his hairy feet.

Poor ape. He doesn’t know it, but he’s destined to lose. Not that he’ll go away. At least I hope no one finds the technology to dispose of him. Without him, humans wouldn’t be humans. (There is a version of transhumanism that seems to expect just that and always strikes me as being as repugnant as the attempt to change humans by political means. The Soviet Man is no more appalling than the poreless god-like man of the future who lives entirely in VR.) But try as he might, he can’t stop innovation and the ever-cascading change pouring down on him. And truly, he should embrace it, because technology will afford him the chance to make his peace with the angel, and to stride forward into the future, if not a more coherent being, at least a happier one.

Societies based on scarcity; societies in which everyone has to live a certain way in order to survive; societies led by a strong leader—all those are trends of the past, trends of the ape-brain. The trends of the future are abundance; societies where you can live your life the way you want, because there is a gadget, a pill, a technique to do just what you wish to without negatively affecting your neighbors or peers; and distributed knowledge and power.

Will it proceed without a glitch? Of course not. Our ape will fight and scream and fling poo. For some time and in some places, he will perhaps manage to hold progress at bay, and probably create quite a dark and dank lair for himself.

But technology will leak even in there. Things will change. The future will march in. In lurches and sideways dodges. In bobs and weaves. The gates are open and it’s too late to shut them. The future is coming. And it’s very bright indeed.

*Sarah A. Hoyt is a writer of science fiction (and fantasy and mystery) which, while giving her a certain interest in trends and effects of technology does not, by any means, make her a prophet or even a Cassandra. Take her predictions as you might. But she would place a strong bet on these.*

A very interesting, and thought-provoking, article (as usual) from Sarah.

The book is, also, excellent!

Thank you, Sean, for letting me post, and thank you Allan.